Engineering an LLM Data Classifier for Enterprise Privacy Governance

A technical deep dive into building a production-ready LLM data classifier using metadata-only inputs, adversarial benchmarks, and precision/recall metrics at enterprise scale.

Shortly after publishing Sensitive Data Discovery with LLMs, I got a call from the creator of one of my favorite open source privacy projects, Cillian Kieran of Ethyca, asking if I wanted to build these capabilities into their enterprise product. Of course I did!

Like me, they had asked ChatGPT to classify sensitive data in a database schema and seen promising outputs. Could these capabilities be taken from the proof of concept stage to a fully realized product?

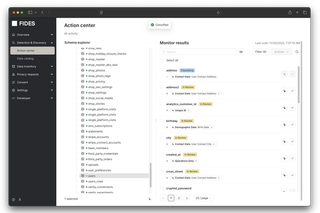

To answer these questions for the Helios subsystem of Ethyca's Fides platform, I set out not just to build an AI data classifier but to engineer one. I developed a quantitative evaluation framework for data classification, built supporting tooling to apply it at scale, and painstakingly applied privacy domain expertise in numerous improvement loops.

The result of this six-month effort is a fully integrated product feature that delivers highly accurate tags across every data category in the Fideslang taxonomy.

Overview

Overall, LLM classifier accuracy benefited greatly from a quantitative evaluation approach. Every classifier accuracy metric (precision, recall, and F1 score) improved from a starting point of around 50% to over 80% against an adversarial benchmark suite. Against easier benchmarks from real-world systems, this accuracy exceeds 95%.

This level of accuracy was achievable with models as small as 32B parameters. On a single GPU, the classifier developed here reached classification rates of 95 fields per minute or $0.603 per 1000 fields. With no dedicated cost optimization effort, a data warehouse with one million fields can be classified from scratch for $603 on cloud inference platforms. Many opportunities remain for cost optimization, which will push this cost down over time.

The most surprising aspect of this project was how much effort went into fixing human labeling errors versus AI labeling errors. In my past experience with data classification projects, significant data cleaning and preparation was necessary before usable results were achievable with automated classifiers. In this work, from Day 1, LLM outputs were better than human labels. Superior to either, however, were AI-assisted human labels. This led me to develop a suite of "tagging copilots" that greatly elevated the quality of the evaluation dataset. It was fun to use these tools, like having an ongoing conversation with eager colleagues that had read case law, Solove, and open source code. The end result was something more than the sum of its parts -- LLM critique and testing pushed me to refine and improve the underlying taxonomy for data categorization, which fed back into more reliable and useful LLM results.

Scope

In this first cut at applying LLMs to the task of data classification, I focused on the task of metadata-only data classification against a standardized, open-source taxonomy using only prompt optimization to improve accuracy.

The inputs for this task are database schemas - column names, data types, and optionally human-provided descriptions of table contents. Notably, table content (samples of the table’s data) are not included.

The outputs are labels of what sort of privacy-relevant data the column contains, if any. The taxonomy for these labels is Fideslang 3.1.1, an open source data privacy taxonomy developed by a consortium of industry contributors.

I focused on metadata-only classification as a uniquely useful intersection between the capabilities of LLMs and the needs of enterprise data governance programs. One of the biggest challenges to deploying data classification at scale is security: how do we mitigate the security risk of a data classifier having access to all sensitive data in the company? By classifying with only metadata, we sidestep this problem, performing classification with the much less sensitive metadata.

Besides deployment practicality, metadata-only classification uniquely suits the capabilities of LLMs. The state-of-the-art for metadata-only classification relies on either brittle regular expressions or on large training sets. Both of these approaches are only capable of identifying columns that are similar to previously encountered columns. LLMs, on the other hand, are able to perform this classification task given only general descriptions of what they are looking for. Exploring just how far it is possible to push this zero-shot capability would demonstrate one of the key advantages of an AI classifier over any previous technology.

The final important aspect of scope was focusing exclusively on prompt optimization. While it is possible that fine-tuning could produce significant benefits, it is orders of magnitude more expensive to implement. Fine-tuning would require a larger testing dataset, result in slower iteration loops, and necessitate more complicated integration at deployment time. While this will be an interesting area for future work, this effort focuses on finding the limits of what is possible with the much lighter-weight technique of prompt optimization.

All in all, the goal is a classifier that runs against any schema with no customization, requires no access to sensitive data, and produces outputs that cover the main privacy concerns of a typical enterprise. No big deal, right?

Measuring Classifier Performance

Step 1: Craft representative schemas to classify

One big resource that Ethyca provided for AI classifier development was their extensive library of synthetic database schemas assembled over the years spent building their FIDES platform. These schemas were fully synthetic (generated without reference to customer data) but informed by hands-on experience seeing how sensitive data flows in a typical enterprise environment – from CRUD applications, to data warehouse tables, to test instances and marketing platforms.

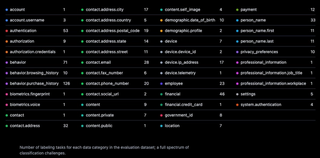

A subset of this testing data was extracted to assemble ~2,000 tagging tasks across 43 different data categories.

Step 2: Produce ground truth labels verified by human domain experts

While there was a significant amount of synthetic schema data to draw on from past work, these data did not include high quality data category labels.

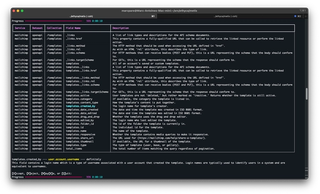

To label the evaluation dataset, I built a custom terminal UI (TUI) to review and label every field in this dataset.

A single pass of human-only tagging was verified by an additional pass of LLM-assisted tagging: any disagreement between a human label and an LLM label were prompted for review. I found that my brain-only tagging was extremely unreliable, as the number of labeled fields grew from 449 to 825 after this validation pass.

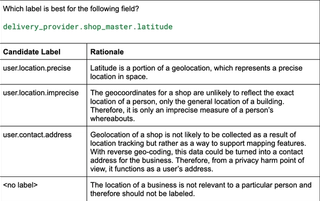

If outright errors were the only challenge, the labeling effort would have finished quickly. However, besides surfacing errors, additional labeling passes revealed numerous tricky edge cases for data categorization that could not readily be assigned a “correct” set of labels. Here’s an example:

I was happy to find that the testing dataset represented such a challenging diversity of test cases. However, it did require me to develop tools and processes for resolving these tagging challenges.

Determining the ideal output of Ethyca’s data classifier is a combination of privacy engineering and product design – what output will be most useful for customers using the platform? As such, I sought engagement from team members that had worked hands-on with customers, eventually settling on an informal Slack-based polling system to gather input asynchronously:

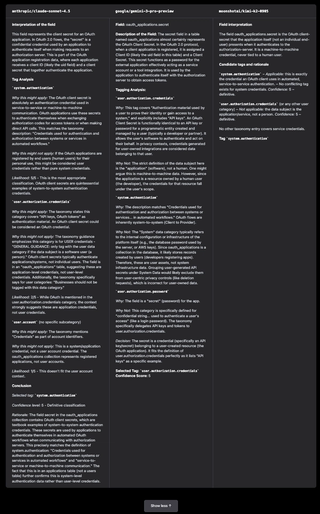

On the tools front, I added an ensemble analysis feature to the tagging workflow. With this feature, I could request that three different state-of-the-art models perform a detailed analysis of a particular data field. Here's an example for a field named oauth_applications.secret. Notice that they don't all agree on the final classification! While it was tempting to fully automate ensemble analysis, disagreements of this sort reveal how important it is to have a human-in-the-loop for building a quality evaluation dataset.

After numerous passes through this process I converged on high-quality ground-truth labels. The benchmark dataset includes examples for 46 different data categories from the Fideslang taxonomy.

Step 3: Define accuracy metrics

If someone tells you their classifier is “99% accurate”, what does that mean? It might mean nothing at all.

Consider a data warehouse with millions of data fields. Let’s say exactly 1,000,000. Typically, privacy-relevant data is only a small fraction of data collected by an enterprise. So, imagine that a generous 14,000 fields end up with a data category tag while the remaining 986,000 receive a default tag that represents “no privacy relevant data categories apply” (this is the system.operations tag in Fideslang)

Now consider a classifier that does nothing at all; it always outputs `system.operations`. You probably see where this is going: if you count every time the default system.operations tag is assigned toward your accuracy, this non-classifier achieves an accuracy of

- 986,000 / 1,000,000 = 0.986 = 98.6%

This is not an exaggerated toy example – this sort of sparse distribution of privacy-relevant data is typical in enterprise. You can see my 2022 talk of data mapping at a self-driving car company that found ~2,000 privacy-relevant fields in a warehouse of 90,000,000 fields. In this case a non-classifier would be 99.997% accurate!

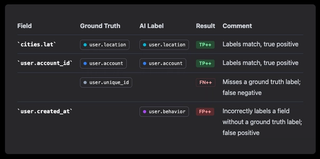

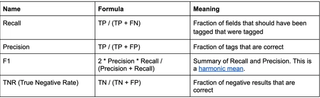

Instead of this intuitive but flawed accuracy metric, we quantify classifier accuracy the following way. First, we count the number of True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) tags:

From here, we compute the following accuracy metrics

These metrics can also be reported on a category-by-category basis, which I implemented in a custom-build workbench for classifier R&D:

These metrics provide a useful way to talk about classifier performance and trade-offs. High recall means “you can trust this classifier to find everything sensitive.” High precision means “every tag the classifier outputs is likely to be correct.” If precision gets too low, then the classifier is likely to not be usable in practice because it will drown out true findings with nonsense.

Results and Insights

With all the tools in hand to evaluate classifier performance, I was able to investigate the following key questions:

- How much can classifier performance be improved from baseline?

- What techniques improve classifier performance the most?

- How big of models are required for suitable accuracy?

- Do LLMs achieve a level of performance useful to enterprise data governance?

How much can classifier performance be improved from baseline?

As a baseline for classifier performance, I started with a barebones prompt:

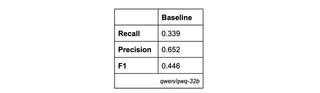

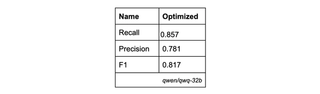

This naive prompt achieves the following performance with Qwen’s QwQ 32B:

I experimented with a variety of techniques for improving performance, from prompt optimization to system architecture, measuring impact to accuracy after each change.

I was able to push accuracy to the following:

These accuracy metrics undersell the performance as improving performance on matching tags exactly also improves the quality of missed tags.

What techniques improved classifier performance the most?

Improvements to the classifier can be grouped into addressing three major failure modes: laziness, shallowness, credulity.

Addressing Laziness – Laziness is the classifier’s tendency to output classifications for a few fields in a table then skip the rest. Initially, I tried adding variations of "carefully review each field" to the prompt. However, this produced no measurable accuracy benefit. Instead, I forced the classifier to consider each field by issuing a separate request for each field to tag. This "one field at a time" system architecture greatly reduced incidence of laziness, and, with requests designed to maximize prompt caching, still kept costs reasonable.

Addressing Shallowness – Shallowness is a classifier's willingness to jump to a plausible-sounding but incorrect solution. Perhaps it sees a field containing the word "latitude" and tags it as user.location.precise without considering that the surrounding context reveals this to be location data for a business and not a person. A simple but effective fix was to ask the model to "output a discussion of tagging considerations." The chain-of-thought tokens generated in the response resulted in classifications that did a better job incorporating less obvious considerations. Interestingly, enabling the "reasoning" or "thinking" flag in models like DeepSeek-V3 or QwQ-32B did not improve accuracy.

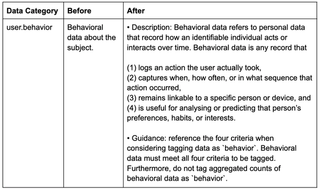

Addressing Credulity – Credulity is both an LLM’s greatest strength and weakness. LLMs will do their best to follow vague guidance, reading between the lines to provide a best effort response. In the case of data classification, this is a problem because vague guidance leads to unpredictable classifier behavior. Data classification is particularly prone to this issue as tagging guidelines are often the result of a committee-driven process, which leads to overly broad descriptions to reach consensus. Addressing this issue meant sharpening tagging instructions with domain expertise. Here is an example of the evolution of guidelines for a data category:

How big of models were required for suitable accuracy?

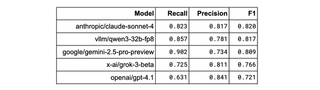

I ran the best prompts against a variety of state-of-the-art models:

I was surprised to find that bigger didn’t always mean better. Very small models, on the order of 18B parameters and lower had outright classification errors that were not possible to fix with prompt changes. However, after about the 32B parameter threshold, accuracy did not improve meaningfully as model size increased.

Different models would end up with different trade-offs in precision and recall, reflecting, roughly, that some models are “more conservative” with tagging while others are “more creative”. Conservative models exhibited higher precision, while creative ones exhibited higher recall.

Intuitively, this suggests to us that there is only so much signal in metadata for classification, and once a critical size of model is reached, all of that signal can be teased out.

Do LLMs achieve a level of performance useful to enterprise data governance?

I also ran this project’s classifiers against real-world datasets provided by Ethyca customers to validate whether the lab-measured performance translated to real-world results. While the specifics of these datasets are confidential, LLM accuracy metrics pushed well over 90% (precision, recall, and F1) in all of these tests. In one notable test, every single LLM tag was correct (100% precision!).

As a further interesting finding, a number of these customer-provided datasets had human labels. In every analysis of divergence between human and AI labels, AI labels were found to be better. Across all of these tests, a positive AI label was incorrect 5% of the time while a positive human label was incorrect 14% of the time.

In every measurable dimension, LLM classifiers were superior to human labelers.

What's Next

Ethyca’s LLM classifier today is only the first step in a long journey of evolution for LLM-assisted data governance. To date, I have focused on the ability to discover sensitive data according to a particular baseline taxonomy with as simple a system architecture as possible. The success at this initial task suggests the possibility of many future capabilities.

Here are some examples of the major areas on my R&D roadmap after this project:

- Scale - How small can we shrink a Language Model to still perform well at data classification?

- Customization - For teams that want to extend Fideslang, how can we enable them with prompt optimization tools to incorporate their custom taxonomies?

- Self-Optimization - Can we optimize prompts in an automated fashion? Emerging research suggests that LLMs are human-level prompt engineers. Internal experiments with prompt optimization by genetic algorithms show encouraging results.

- Extension - Can we extend beyond data category categorization into data subject and data use categorization?

- Implications - What new use cases are enabled by such large-scale and diverse data tagging that were limited by the difficulty of getting humans to keep labels up to date?

Zooming out, a fascinating finding from this work is how LLMs lower the barrier to entry for users to interact with automated classifiers. In the past, improving classifiers meant fiddling with brittle regular expressions or running ML pipelines. With LLMs, a non-engineer can dramatically change the behavior of a classifier on the fly – no expensive re-training required, no special syntax to learn. It will be fascinating to see the impact of privacy domain experts that were previously hampered by technical barriers now able to see their expertise unleashed at scale against real data infrastructure.

If you are responsible for AI systems that depend on data you cannot reliably classify or audit, the next step is to evaluate whether your existing data foundations can support production AI at scale. Ethyca is building the underlying infrastructure to make data classification, governance, and enforcement measurable, automatable, and repeatable across real enterprise systems.

If this work resonates with problems you are actively solving, we are happy to compare notes or walk through how these approaches are implemented in practice. Set up time with our engineers here.

Ethyca builds the data layer for enterprise AI, providing system-level privacy and governance primitives that integrate directly into modern data and application stacks.

.png?rect=0,3,4800,3195&w=320&h=213&auto=format)

.png?rect=0,3,4800,3195&w=320&h=213&auto=format)